Faith & Celebration

Yom Kippur: when tradition claims continuity while meaning completely transforms

When you’re Muslim and your coworkers want you at the Thanksgiving table: the hidden textual war over gratitude in Islam

The architecture of sacred time: how different countries calculate easter and why it reveals the machinery of religious authority

Saint Patrick’s Day beyond the green: how religion, nationalism, and diaspora turned a christian feast into a global political symbol

Religions

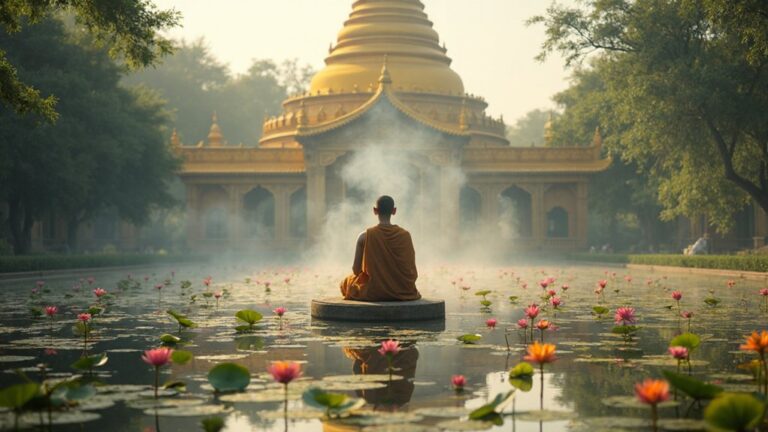

When Buddhism faces its greatest dilemma: religion or philosophy? And why the answer changes inside a meditation hall

The abyss between worlds: why Mormonism and Catholicism represent irreconcilable metaphysics, not mere doctrinal disagreement

The question that breaks itself: why “are Jehovah’s Witnesses Christian?”Reveals something fractured at Christianity’s core

Beyond the textbook trinity: what really separates Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana

Soul

Faith and mental health: what research actually says (and what it doesn’t)

When faith-based charities become corporations: the hidden costs of growth, structure, and digital ministry

When faith becomes a problem: the hidden costs of meaning-making during crisis

The architecture of hidden meaning: why western modernity created “esotericism” and how institutions control sacred symbols

Most Recent Articles

The question that breaks itself: why “are Jehovah’s Witnesses Christian?”Reveals something fractured at Christianity’s core

For those curious about the faith of Jehovah's Witnesses, their unique beliefs challenge traditional Christian...

January 13, 2026 at 1:57 PM

When you’re Muslim and your coworkers want you at the Thanksgiving table: the hidden textual war over gratitude in Islam

Just what influences some Muslims to forgo festive celebrations, and how do these choices reflect...

January 9, 2026 at 7:55 PM

The architecture of sacred time: how different countries calculate easter and why it reveals the machinery of religious authority

Uncover the reasons behind the varying dates of Easter celebrations worldwide and discover how calendars...

January 9, 2026 at 6:29 PM

Beyond the textbook trinity: what really separates Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana

Get to know the three main types of Buddhism, Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana, and discover...

January 9, 2026 at 4:00 PM

Saint Patrick’s Day beyond the green: how religion, nationalism, and diaspora turned a christian feast into a global political symbol

Saint Patrick’s Day is often perceived as one of the most accessible cultural celebrations in...

January 9, 2026 at 3:18 PM

Buddhist non-theism is a lie: what I discovered when I stopped accepting the textbook explanation of what Buddhism actually is

Discover insights that could transform your spiritual journey.

January 9, 2026 at 12:58 PM

I sat with a Hindu Priest and a Buddhist Monk for six hours. Here’s what they revealed about why their traditions can’t agree on anything, including reality Itself

It was 9 AM on a Saturday morning in a rented conference room in Boston,...

January 8, 2026 at 4:00 PM

I thought Buddhism was universal until I looked at the history: what the West needed to believe and why

I thought Buddhism was universal until I looked at the history: what the West needed...

January 6, 2026 at 9:00 AM